"If a part of the discourse is missing, you need to create it yourself."

Marge Monko (1/2023)

Marge Monko in conversation with Paul Kuimet.

Marge Monko (MM): To be completely honest, I struggled with preparing for this conversation – the war in Ukraine has really consumed my thoughts. It is extremely difficult to concentrate on anything else. But I feel that working on something in-depth is also therapeutic and perhaps even political.

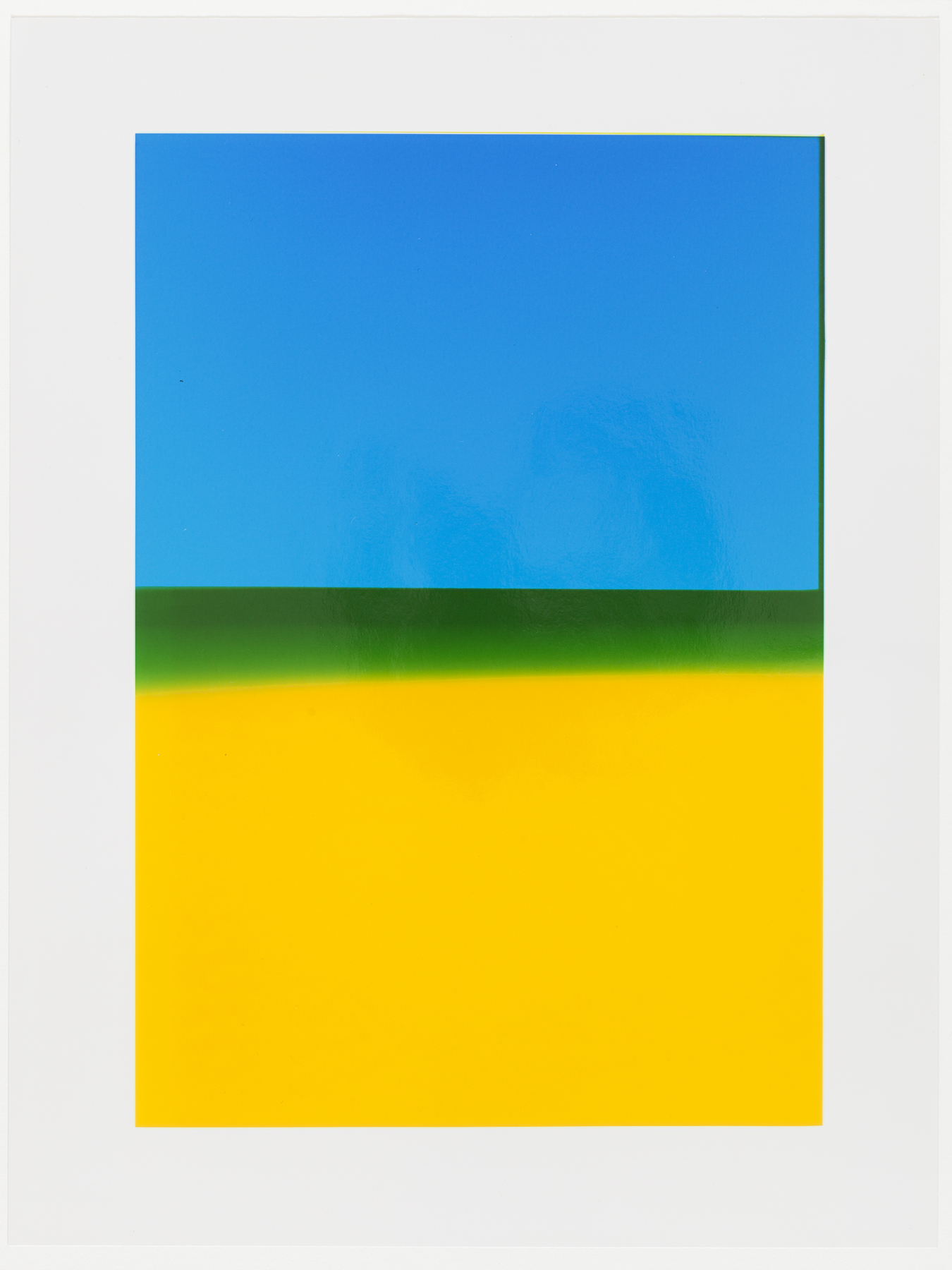

Paul Kuimet (PK): Yesterday, I sat in the darkroom making colour luminograms. I tried to get the colours of the Ukrainian flag onto paper with the idea of making a set of works that I could sell at a good price and for a good cause. Alongside the war, I also thought about the meaning of the symbols of a state. I contemplated if I really wanted to create something that is so clearly linked to national symbols.

Paul Kuimet

Untitled (for Ukraine) 2

2022

Series of 10 C-prints (luminograms), 41 x 31 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Regarding the overall situation, we do live in a time of crisis as it is. I read the cultural weekly Sirp this morning, where the young artist Nele Tiidelepp came to the conclusion that the mentality of her generation is: everything is "shit" but creative work is a little bit less "shit".

MM: Well said. You and I have interviewed each other several times, but today I'd like to discuss materiality and image. Photographs are also very much material objects, at least in the sense that we work with them in our artistic practices. Yet, I feel that whenever photography is written about or discussed, this aspect is often overlooked.

PK: Historically, it really is the case that, when it comes to sculpture, material is discussed more, and with painting it is also done to an extent but considerably less. Yet, there is still a difference, whether it's oil or acrylic, tempera or fresco, or what have you. But photography is like a window that people look through. They don't even differentiate between images reproduced in a book or on a screen or in an exhibition.

When we talk about art, it concerns three-dimensional space with objects made to specific measurements. Another thing is differentiating between the technical side of printing, which can broadly be divided into two: photographs printed from digital files and photographs that are enlarged from negatives using analogue technology. At one point I started feeling that I would like to maintain a physical contact with the materials I work with. When working in the darkroom with analogue techniques I can do this.

MM: I feel the same. This conscious need to be in contact with material has been very much on my mind for the past ten years. I have felt the need to manually work through the process. This is a completely different experience from digital printing. When I was enlarging the photos for my last series, "Window Shopping" (2014–2021), which consists of twenty colour photographs, I understood that probably 99% of the viewers couldn't care less about how the works are printed. Maybe one percent of the viewers understand what it means and values it. But it was still important to me to make these prints using an analogue method.

Marge Monko

Window Shopping

2014–2021

Series of 20 C-prints 60 x 60 cm and 10 photo lithos 35 x 30 cm

Installation view in Kai Art Center

Photo by Mari Volens

Courtesy of the artist

PK: My process is that I take photos and develop the negatives and then scan these in my studio for previews. From these files, I print small, approximately ten-by-ten centimetre images, I look at them and decide which ones I want to keep working on. I have seen the image on a computer screen but if I'm lucky, if I begin printing the image and it finally emerges from the processor on paper, I see something I didn't know was there before.

There are painters who also say they paint to discover something new, something that is impossible to sketch out beforehand. There are aspects that are truly revealed only when you really start working with your material. Now, if I think about my series "Crystal Grid" (2020–...), which is ongoing, I feel that the relationship between the image and the material that carries that image is expressed in certain ways. For example, I have noticed that I have increasingly moved closer to the depicted plants.

MM: I think we can discuss materiality through certain elements you have photographed. One such element being glass. You have several works where you look through the window, so to speak, or look at a glass facade as surface. My "Window Shopping" series is also about looking in from the outside, but the surface of the glass standing between the interior and the exterior plays a key role.

I discovered that these images also include a third layer only when I was printing these photos in the lab. First, the display at the window; second, the facade and the glass that separates us from the display; and third, the reflections. When looking at these images closely, the reflections on the glass surfaces allow us to see what is standing opposite the window across the street.

PK: Glass architecture leaves the impression of being very light and airy – clouds and sky are reflected on its surfaces, yet we can not see behind it. So, it simultaneously feels very light and, in a way, transparent – yet most of the time, it conceals what is on the inside.

In turn, I have noticed that you have been fascinated with everyday objects that you also use in your art, the latest occurrence being the installation "I Don't Know You So I Can't Love You" (2018/2020), where two virtual assistants speak to one another.

MM: Since my work "I Don't Know You So I Can't Love You" discusses contemporary forms of intimacy, like long-distance relationships, virtual assistants as a conceptual choice made sense. Many relationships today are formed and maintained through text, either by written or verbal communication, without the physical component. I was inspired by a YouTube video, where two smart devices, named Mia and Vladimir by Google employees, profess their love to one another.

PK: Of course, Mia and Vladimir remind me of "Nataša and Saša" (2022), which I recently saw at Hobusepea Gallery (Marge Monko and Maruša Sagadin, "The A. B. C. D. E. F. G of Love", 13. I–7. II 2022). These images also speak a very pop-art-like language as the surfaces display the printing raster revealed in the process of scanning. In addition to that, they also refer to appropriation art.

MM: One of the methods I've used since 2014 is appropriation. In that sense, there really is a connection between "Nataša and Saša" and pop art. Both of these portraits were scanned from the packaging of Soviet-era colognes. I remember their faces from my childhood – I liked the man on the packaging of Saša a lot. What is interesting is that both of these models are more of a "Western" type, even though the products were clearly meant for the Soviet Russian market. Here we can once again see Russia's ambivalent relationship to the West. I thought it interesting to show these two iconic Soviet-period portraits in the context of the Western mid-century appropriation, to exhibit them as lovers.

This practice of appropriation began for me with the series "Untitled Collages" (2014) and "Ten Past Ten" (2015). The source material for the first was a set of negatives originally photographed to advertise jewellery that I bought off eBay, and the second is based on magazine ads for watches. Hands have, in fact, been the central motif in my appropriated images. If Aristotle describes hands as tools that are capable of making new tools, advertisement photographs use hands as tools for presentation that elevate and hold products, indicate scale, etc. For example, in advertisements for stockings, hands are particularly important in demonstrating transparency and elasticity. In the works I have created for public space, I have specifically used commercial photos of stockings.

The choreography of the video "Sheer Indulgence" (2021) is largely based on the aesthetics of 1970s and 1980s stockings commercials. This is sort of like a remix. But it also includes references to a few historic episodes or phenomena relating to stockings.

PK: In a way, the film is also very tactile. And the use of film creates a certain kind of density of image.

MM: Since I have worked with stockings for around seven years and bought various related products from eBay in order to get the packaging for photograms, I have a large quantity of these and I can say their materiality is highly appealing. For example, when you look at stockings from the 1930s, these look very elaborate, almost handmade, with a lot of emphasis on detail.

PK: And this is how we get back to materiality again. There are three materials present: photo paper that carries the work; the packaging with its semi-transparent opening that creates the image on photo paper; and inside the packaging there are the semi-transparent stockings. For me, these things are very much present but has anyone ever written about that?

MM: No. Surprisingly, I often need to explain what a photograms is. These leg and foot shaped openings in the packaging are there so that the consumer can see the texture of stockings, to demonstrate the materiality. When using these to make a photogram in the darkroom, some cardboard packages are thick enough that no light goes through and so we only see the silhouette of a black leg or foot on a white background. The thinner the material, the more information comes through from the packaging, which is why the photograms look different.

PK: Critics' vocabulary is different and is largely dependent on personal interests. And if the artist feels that a part of the discourse is missing, you need to create it yourself, just as we are trying to do here.

MM: You have often used 16 mm film a lot – something that very directly relates to materiality. I feel that this is my medium as well and I would like to use it more but it is also very tiring, as it is so labour intensive. I mostly work with a team for a short period of time during shooting, but the process of post-production is sometimes exhausting because there is no money, which is due to the fact that there is no producer. And we all know why – in the local art field, we have not managed to find people who would be interested in producing artist films, not to mention financing them. There is a palpable lack.

This is why I have periods where I create works I can more or less make alone. I have the video "Dear D" (2015), which I screen-recorded on my computer. I made a plan for what I needed to do on that screen, what programs and windows I needed to open and in which sequence, and then I recorded it. Very little editing was done. The extent of post-production was such that we recorded the voiceover of the video in a recording studio.

PK: I suppose it is a balancing act between the artist's vision of what they want to achieve and how they want to work.

MM: You have several works where you have focused on image and consciously cast sound aside.

PK: In some ways, this is inspired by people whose work I admire, like Mark Lewis and his pictorial filmmaking. He says that the sound that accompanies moving images shifts the attention away from the pictorial. And when we look at his work, we hear what is going on without actually hearing the sound. In a similar manner, we should "hear" sound when we look at paintings or sculpture.

But we also wanted to talk about making monographs. I finished making mine last year and I had to go through the works I had created in the past eight years, most of which ended up in the book "Compositions with Passing Time" (2021) as well. When I was looking at all these works during that process, and was in a bad mood, I was very much aware of which works could have only been created by me and which ones are more mediocre and could also perhaps been created by someone else just as well. But when I'm in a more positive mood, I comfort myself with the thought that the mediocre works are necessary for the more significant ones to be born at all.

MM: I think this is a beautiful consolation.

PK: And on the other hand, there have been exhibitions where I have not been so sure about certain works but then someone else comes and says that this work in particular touched them. Then I again realise that not everything depends on me and how I judge my own works. We all want to have at least some control over things. But that is not always possible.

Marge Monko has studied at the Estonian Academy of Arts (MA in Photography, 2008) and the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. Her works can be found in several public collections (MUMOK – Museum of Modern Art in Vienna, Muzeum Sztuki Łódź, FRAC Lorrain, Fotomuseum Winterthur, Art Museum of Estonia). In 2012, she was awarded the Henkel.Art.Award.

Paul Kuimet studied photography and video at the Estonian Academy of Arts (MA in Photography, 2014), the University of Art and Design Helsinki, Baltic Film and Media School, and the University of East London.

This conversation took place on 10. III 2022 at Marge Monko's studio.

Read the full version (English translation by Keiu Krikmann) from Marge Monko's new book "Flawless, Seamless" (2022).

< back