"Nothing is more important than this sentence"

Indrek Grigor (2/2015)

Indrek Grigor takes us on a thorough guided tour of the exhibition "City of Dreams. Text Art in Tartu 2002–2015".

Tartu Art Museum

10. IV–31. V 2015

Artists: Anna Hints, Madis Katz, Kiwa, Erkki Luuk, Martiini, Barthol Lo Mejor, Taavi Piibemann, Tanel Rander, Martin Rästa, Toomas Thetloff, Jevgeni Zolotko.

Curator: Kaisa Eiche.

"Tartu 88"

It is not easy to discuss the text art exhibition at Tartu Art Museum curated by guest curator Kaisa Eiche, since her motivation for certain choices when it comes to the content of the show are difficult to trace. On the one hand, the museum commissioned it as part of their curatorial archive-based project "Tartu 88", the aim of which is to create a thoroughly researched archive that would contribute to the museum's earlier selections, as the museum's website states – an important role this exhibition and its public events should therefore perform is to make the process of collecting visible and understandable. "City of Dreams" is the third exhibition in the archive-based series, yet its engagement with the archival project is equal to the position of "Tartu 88" in the show's information graphics and the amount of financial support it received from the Estonian Cultural Endowment – basically zero.

If the first show "Cardigans and Kostabis: Tartu Exhibition Sites 1990–2014"1 presented the audience with a rather clear overview of the materials collected in the archive, and it could be said it was – more clearly than in most museums – an exhibition based on art historical research, the second archive-based exhibition "Typical Individuals. Graffiti and Street Art in Tartu 1994–2014"2 was unable to communicate itself to the audience without the accompanying text, even though the curator's statement did focus on collecting and conceptualising, and it had very little to do with the project's overall goals of composing an archive and researching it. The latest show in the archive-based "Tartu 88" project, "City of Dreams" does not include any archival materials in the exhibition at all. This aspect of the project is only referred to through the work of Erkki Luuk and Martiini, which are shown in a display case, and as such play with a medium typical of museums. In every other sense the exhibition is no different to any other show mapping art history, in whichever gallery or museum.

The fact that projects often go beyond their expected scope and take on new characteristics is no surprise and is often beneficial; however, in this case it seems as if "Tartu 88" keeps tripping over itself. It should be an exhibition series that draws the focus of both the audience and the curators to the archives, yet the curators seem to be avoiding a systematic approach to the archives and as usual base their choices on aesthetic preferences. So their unwillingness to consider the theme of the series as a structuring guideline causes unwanted complications: when it comes to "Typical Individuals" it was clear that the curator Marika Agu who had recently curated a notable street art exhibition at Y-Gallery and had just commissioned a display from stencil-artists for the exhibition "Is This the Museum We Wanted?"3, faced the danger of repeating herself. Currently, the only work in the collection of the national art museum by a street artist – Edward von Lõngus – had already been exhibited twice at the Tartu Art Museum over the last year4, so a new approach had to be found. The need to organise a street art exhibition was dictated therefore by the systematic nature of the series, not by a change in the local street art scene. Presenting the exhibition as an archive; that is, following the example of the first "Tartu 88" show, would have helped to preserve the series as a whole and provided a more consistent line to tie the exhibition together than the concept the curator came up with – framing street artists as flaneurs, which may apply to street artists of the 1990s, but fails to encompass contemporary artists and practices.

This is also where "City of Dreams" trips up. Street art has been the most important or at least the most visible part of text art in Tartu. Although through graffiti and tags, street art has traditionally been centred on text anyway, stencil art in Tartu has also been strongly influenced by literature. And not only by featuring direct quotes (long white displays with quotes from literary classics are not rare in Tartu), but also when it comes to the visual side: Anton Hansen Tammsaare, Lydia Koidula, Robert Walser, "The Little Prince", Arno and Toots, "Emperor's New Clothes", etc. But all of this has been left out of the text art show by the curator Kaisa Eiche and the reason seems to be that street art is over-exploited as it is. This can be understood, of course, when we put it in the context of this particular series of exhibitions; however, ignoring street art in the curatorial text exploring the nature and development of text art in Tartu seems like an intentional distortion. If the "Tartu 88" exhibitions had followed the logic of the series with its inevitable repetitions caused by the theme and their sequential nature, and focused on creating links between the shows and establishing this as their structural mechanism, the intersections between the exhibitions that are now being largely ignored, would have instead added value.

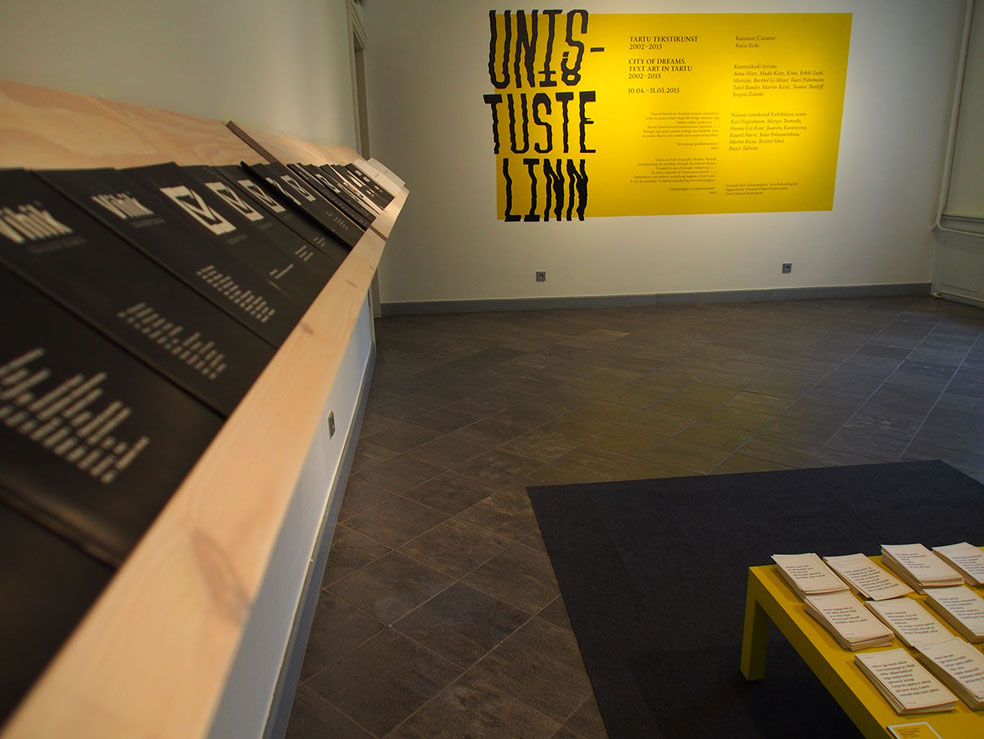

"City of Dreams"

Exhibition view at Tartu Art Museum

photo by Marika Agu

Department

The curator Eiche rightly points out that the majority of the artists taking part in the show are connected to the department of photography at the Tartu Art College, and this is also how the curator and artists in the show are linked to each other. But an even larger circle of names (not only the participating artists, but others whose works are on display in the "reading room" of the exhibition) are connected to each other through the semiotics department at the University of Tartu: that, among other things also connects the charismatic professor of the photography department Peeter Linnap, the curator of the exhibition and the author of this review. Tracing the context also helps to explain one of most important characteristics of text art in Tartu – its academic nature. The academic quality also means text art in Tartu is rather traditional in its choice of format – text is not incorporated into visual art, instead the artists play with the syntax of the language (in a broad Structuralist sense) and the semantic qualities of speech.

One of the most obvious, although not necessarily one of the best, examples if this attitude is Kiwa's "Alphabet without A" (2008), which – like a proper canonical artwork should – is painted on canvas. In order to make sense of the meaning of the work one has to understand language as a mechanism for structuring reality and the alphabet as one of its fundamental models. While Kiwa plays around with the canon as such by transferring the alphabet from paper to canvas, most text art in Tartu can be found in books and magazines with a traditional format. In his five-volume "Truth and Justice" (2007), Toomas Thetloff deconstructed the words from one of the most significant texts in Estonian literature, the five-volume work "Tõde ja õigus" (Truth and Justice) by Anton Hansen Tammsaare, in order to experiment with perception, yet he still maintains the book format.

Due to the proximity of academia, not only do the works display a notable degree of academic qualities, but sincere student-like attitudes as well. Taavi Piibeman, whose series "References: Punctuation Marks from the Ends of Essential Texts" (2004) was created during a course titled "text and image" taught by Andrus Laansalu (alias andreas w), said about his own work with a smirk: "This is genius, I will take a picture of the text." Anna Hints's "Altar for Post-structuralism" (2008), which does not focus on the endings of texts but on the blank spaces between words in a manuscript, was probably created during the same course.

Publishing house Tartu

Alongside the mental spores of the written medium that sync with academia – to use the words of the curator Eiche – there is another common denominator between the text artists who oftentimes seem to stand light years apart from each other – they share a common demographic and psycho-geographic ground. Most of the artists still active, live and work in Tartu and are a latent part of the psycho-geographic sect that worships the city, whose actions are manifested in the collections of fiction at the exhibition's reading room – "Mitte-Tartu" (Non-Tartu, 2012, ed. Sven Vabar) and "Tartu rahutused: valik jutte" (Anxieties of Tartu: Collected Stories, 2009, ed. Berk Vaher). This tendency is articulated in a visual form by Barthol Lo Mejor, with his set of postcards "Survival Guide for Small Town Living" (2015). Some of them are too obvious and simple: "Close the curtains and listen to the sound of the ocean" or "Forget your name and pick a new one". But if read as sentences from the stories of the local master of metaphysical realism, Mehis Heinsaar, they acquire a new meaning.

In her curatorial statement, Eiche writes that dreaming is a significant mental function for all the artists, and she is not wrong, yet the multifaceted nature of dreaming should not be underestimated. Martiini, closely linked to Heinsaar, presents us with incidental and Zen-Buddhist-influenced objects, whereas Tanel Rander, who has once again stepped into the phenomenological absurd, has successfully translated the same approach into the language of decolonial theory and is not hiding his aspirations to communicate with a broader (international) audience. The publishing house ;paranoia, established about a year and a half ago by Kiwa, also has clear international ambitions; however, its publications were exhibited in the reading room, albeit not as part of Kiwa's text-based art practice.

Above I mentioned a text cult, but there are at least two artists in Tartu who want nothing to do with such heresy. The most orthodox of the two is Yevgeny Zolotko, the only "book person" on the text art scene. To him the textual mass overtaking the world is a sign of the apocalypse. In a group show5 at Kumu in 2012 he exhibited a temple curtain made of papier-mâché that was torn when our Saviour died on the cross for our sins. His work "It's Time to Take the Ceilings Down. A Work for Ten Critics" (2010), which also belongs to the collection of the Tartu Art Museum, was recreated for the text art show; the first time it was exhibited was at the 2nd Artishok Biennale6 at the Tartu Art House, where the title functioned as a reference to the biennale's format which required all ten participating critics to write about Zolotko's installation as well as the other 9 works chosen for the event. "Too many words!" is what the work unambiguously states. A similar sentiment is evident in Madis Katz's "Concept Jar" (2012/2015). If the viewers want to know what the work is trying to say, they can reach their hand inside the "lottery jar" and draw an explanation of the concept. Katz has used the jar many times and the snippets of texts have various origins. For example, in "City of Dreams" he draws the concepts from fragments of texts written about his series involving clothing covered in dirty slogans titled "Dare" (2012) by the ten critics for the 3rd Artishok Biennale7.

Both artists doubt the seemingly inherent value and meaning of text, yet still abundantly use it in their own work. What is significant for Zolotko is the canonical nature of the text (religious texts and the Golden Age of Russian literature), whereas Katz as a designer uses text as a design element.

Typography

One aspect that has not been addressed when it comes to text art in Tartu, neither in this exhibition or in a broader context, is its links to the "iconoclastic" text-centred school of graphic design in the Netherlands. Dutch influenced design has a sufficiently important place in Estonia that at the pretentious survey show "Archaeology and the Future of Estonian Art Scenes"8, one of the curators, Kati Ilves, presented it as a scene in its own right: the Tallinn–Amsterdam graphic design axis. At the same time, text art in Tartu was presented as a scene as well, yet characterised as a purely local phenomenon. True, Eiche has included design in the show by exhibiting Martin Rästa's poster "ProtoEclectika" (2006) – a pre-event for the Eclectica event of 2006 – and as a second example, Madis Katz's clothing series with provocative messages, where the typeface and the positioning of the text dominate the message. But it seems that the role of the mythology of Tartu in analysing local artistic practices is so strong that even tendencies without a local-historical tradition cannot be linked to a broader art context. Nevertheless, finding and acknowledging parallels is absolutely necessary for understanding a phenomenon.

An example of the fact that this is not a mission impossible is the recent solo show of Tallinn based designer Margus Tamm, who also studied at the Estonian Academy of Arts, titled "First Three Minutes" at the Tallinn Art Hall Gallery9. Tamm's graphic works were literary and purely text-based, yet his "unsuitable origins" excludes him from the Tartu text art circles, since the latter only exists in the exclusive psycho-geographic space called Tartu. Once again, this is one of those instances where the forced separation of text based street art sets limits on the material Eiche has presented, as street art has been quite influential outside Tartu as well and international idols and contacts are well respected and known, while there seems to be an attitude that text art in Tartu was born out of its own genius. This is not to scold only the curator of the exhibition but above all critics in general, myself included, since I, too, have once described the art scene in Tartu after the 2000s as a self-sufficient system, in a book ambitiously titled "The ABC of Art in Tartu".10

One of the reasons behind the (absurdly) slanted view on text art seems to be the repeatedly mentioned academic background of text artists and their practices. This is so direct, yet so removed from art, that the international authorities in the field, the discursive practices and the academic context with its issues that provide the background for text art cannot be encompassed in the discourse of contemporary art critique. In Estonian art slang, the words "Tartu semiootik" (semiotician from Tartu) denote an obscure and incompetent phenomenon within the context of contemporary art, yet in international academic circles the Tartu Semiotic School is valued and respected. And the complete disconcert is mutual: there is a painting department operating at the University of Tartu, focused on teaching visual art, even though the university has been trying to eliminate it for years, and for rather obvious reasons – the painting department does not engage in research in the traditional sense. So the university considers it a pointless and parasitic institution. Since this attitude has nothing to do with the quality of the teaching and the art that is created there, it also acts as "an official position" of the University of Tartu on all kinds of artistic activities.

1 "Cardigans and Kostabis: Tartu Exhibition Sites 1990–2014", curator Triin Tulgiste. Tartu Art Museum 25. III–1. VI 2014.

2 "Typical Individuals. Graffiti and Street Art in Tartu 1994–2014", curator Marika Agu. Tartu Art Museum 7. XI 2014–1. II 2015.

3 "Is This The Museum We Wanted?", curators Rael Artel, Marika Agu, Mare Joonsalu, Hanna-Liis Kont. Tartu Art Museum 23. I 2014–16. III 2014.

4 Ibid.; "Losers", curator Peeter Talvistu. Tartu Art Museum 12. IV–2. VI 2013.

5 "Speed of Darkness and Other Stories", curators Eha Komissarov and Jaakko Niemelä. Kumu 13. VI–30. IX 2012.

6 II Artishok Biennale curator Kati Ilves. Tartu Art House 2.–11. IX 2010.

7 III Artishok Biennale, curator Liisa Kaljula. Contemporary Art Museum Estonia (EKKM) 10.–20. X 2012.

8 "Archaeology and the Future of Estonian Art Scenes", curators Eha Komissarov, Hilka Hiiop, Kati Ilves, Rael Artel. Kumu 19. X–30. XII 2012.

9 Margus Tamm, "First Three Minutes". Tallinn Art Hall Gallery 11. IV–11. V 2014.

10 Indrek Grigor, Nullindate traditsioonita tendentsid. – Tartu kunsti aabits. Tartu: Tartu Kunstnike Liit, 2014, pp 134–157.

Indrek Grigor is an art historian, critic and curator. He works as the gallerist of the Tartu Art House and is one of the hosts of "Kunstiministeerium" a programme on the Estonian radio station Klassikaraadio.