Peasants At The Temple Of Art

Helena Risthein (3/2015)

Helena Risthein takes us on a tour of the international exhibition "The Force of Nature. Realism and the Düsseldorf School of Painting".

3. VII–8. XI 2015

The Great Hall at Kumu Art Museum

Curator: Tiina Abel

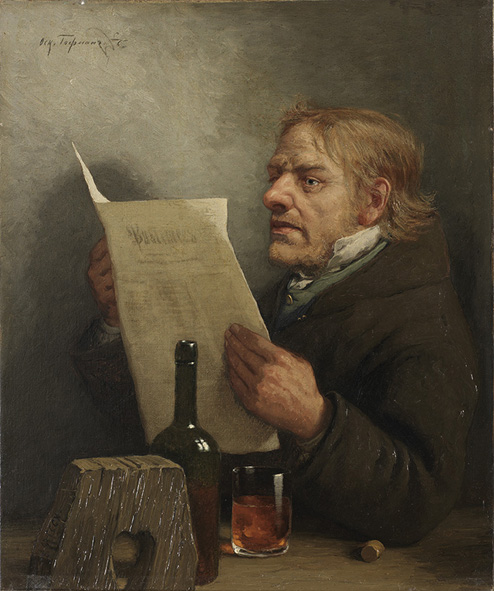

Kadriorg and Rocca al Mare, marvellous places, from time to time come together in principle. This was so a few years ago, on the day for celebrating bread, when a peasant family was having breakfast in the atrium at Kumu and everyone that was interested received natural leaven. Now, the Great Hall at Kumu has an exhibition of the masters belonging to the Düsseldorf School of Painting. Just like an old acquaintance at an official gathering, Oskar Hoffmann (1851–1912) waves at us. He has depicted many of those who could be working their fingers to the bone at Sassi-Jaani farm, elevating their soul at Sutlepa chapel or playing cards at Kolu tavern. Hoffmann's boldly unrefined legacy stands out especially now when it is surrounded by tens of artists from the Nazarene naturalists to the painters en plain air.

Thanks to the lexicons and catalogues of many different eras, along with the indispensable research by Ama(nda) Tõnisson from 1936, we can sketch a picture of the Baltic German painter's life. Since childhood, Tartu-born Oskar was captivated by the peasants he often encountered at the market place. Nearby, were the houses owned by his parents, as well as their bakery. At the exhibition, we find a view of Tartu market. In addition to the bakery business, his mother Emilie Aurora was involved in charity work with the famous pastor, writer and composer, Adalbert Hugo Willigerode (1818–1893). Oskar's uncle, August Frischmuth, was among the painters who decorated the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg. The much loved baker's wife also loved to spend a month in Saint Petersburg each year, visiting the opera even more often (by horse). To celebrate his confirmation, she took her 16-year-old son with her – a poor student at school but talented in drawing, he once attempted to build an organ, for instance. There, Oskar became fascinated by the treasures of the Hermitage and chose to become an artist.

Düsseldorf was believed to be the most suitable place for his studies since many Estonians had succeeded there – as our exhibition confirms. Rather than by his actual professors, Eugen Dücker and Eduard von Gebhardt, Oskar was influenced more by Gregor von Bochmann (1850–1930). There are similarities in their choices of theme and colour, as well as the lively brushstrokes. After attending Düsseldorf Art Academy, Hoffmann travelled around Europe, studied briefly in Paris and lived a few more years in Düsseldorf by the river Rhine, but had indeed started working in Saint Petersburg by 1883. He died in his sleep in a nearby town, Novaya Derevnya, in the year 1912.

In his youth, Oskar had been interested in photography, and during his best years, appeared in photographs himself, taking the hand-in-waistcoat pose or enthroned in a fine studio. For a long period, he lived in the houses of the millionaire Grigory Yeliseyev, being mostly in debt for his rent. He also happened to use the quick loan tactic, among others asking for paintings given to friends as gifts to be returned to settle his debts. Much of his money was spent chasing women, even though he had found the one and only, the woman of the "golden ratio" who he inconsolably mourned over – the famous beauty Emma Wendt. She tried to leave the rake but could not resist her love for him, and returned.

At the time, there were more Estonians studying, working or looking for work in Saint Petersburg than in Tallinn. And there they could be photographed or invited to sit for a painting. The peasants probably waited and wondered when the work would start. Wages in hand, they would leave baffled, shaking their heads. And where did the paintings end up? They hung in the fancy salons of the empire's capital, surrounded by wide golden frames. The paintings of the Düsseldorf School were sold in many places from Riga to New York. The countries of the former Soviet Union should also be explored for examples.

Hoffmann is so much one of our own that he seems to be thinking in Estonian. Apparently, that is not true. However, in one of the paintings from 1887, he has written the following rather clearly: "RIKAT JODIKAT" (somewhat faulty Estonian for "rich drunkards" – Ed.). Many of the paintings from his maturity, depicting peasants with worn-out hats and even beggars, bear the proud line: Hoffmann fecit, opus (followed by some three-figure number). In Saint Petersburg, Russian was expected; hence, the multilingual signature: ОСК. A. Гофманъ fc. CCXCI.

The exhibition includes the work of the first Estonian photographer, Reinhold Sachker (1844–1919). A whole gallery of 19th century peasants fits into two showcases in front of which the viewer must bow. The most memorable is "Vallavaene Valt Tähtvere vaestemajast" (Beggar Valt from Tähtvere almshouse, ca. 1900). Peeter Tooming has written that Hoffmann and Sachker were co-workers. Of course the watercolour portraits and small painted scenes in oils differ from the photographs – they are painted by hand, have soul and are larger than the photographs of the time.

Mostly, Hoffmann depicts people in the foreground, more or less from the chest or waist up, but in one especially outstanding picture there is an exquisite tavern with the whole counter and all of its guests. The light penetrating the bottles and the glasses comes from the window and a modern lamp on the ceiling (Hoffmann also performed experiments with electricity). Tõnisson has written that this artist, who produced numerous paintings in no time if he happened to be in the mood for it, was left-handed and could use both his hands alternately. In his later years, he exercised freehand painting, using no preliminary outline. The gleam of coppery hues somewhat resemble the fellow townsman Julius Klever's (1850–1924) methods, with whom he painted the salute in Moscow, spending the fee before completing the commission.

For a while, Hoffmann was called the "Estonian Rembrandt". This might not be fair to the master, but there are some parallels – in the treatment of light and shadow in paintings as well as etchings, which they both practiced. Both can be characterised by a respect for the genuine, ancient and wise. In the Hermitage, Hoffmann had often seen the best paintings and graphics of the famous Miller's Son and was himself a grandson of a Mecklenburgian miller. He was a member of the Aquatint Association and was granted the status of "Free Artist" by the Imperial Academy of Arts.

Observing his large-scale oil paintings and their uneven surface, I am suddenly reminded of the contrast of light and dark in an old sepia photograph. By Hoffmann's lifetime, many of the works of the Golden Age of Dutch painting conveyed the same tonality – due to the dimming of the varnish. Franciscan brown and grey "gallery tones" were now regarded as dignified and even noble. The choice of tone is often supported by the choice of subject matter. "The brownish-grey colour scale of the Düsseldorf realist painters blended well with the colours of the local peasants' everyday objects and clothes," says curator Tiina Abel, who has been working on the Düsseldorf realists for a long time. When the whole museum was still situated at Kadriorg Palace, she put together an exhibition of our own Düsseldorf representatives in 1980. Lehti Viiroja had exhibited Hoffmann's work at the same venue as early as 1954. Not too long ago, the museum was still headquartered in the Estonian Knighthood House (which, in my opinion, would be a suitable location for the museum of Baltic German culture) and there, too, an exhibition titled "Hoffmann fecit" was held in 2002, the curator Anne Lõugas.

As far as – as it is often referred to – "discovering" the Baltic German legacy is concerned, the Art Museum of Estonia has always been active in presenting it, such as in Moscow in 1956, in a series of exhibitions (by the author of this article) in Tallinn at the beginning of the 1980s, and in Kiel in 1986. Temporary and permanent exhibitions of 19th century art are being continually held. Without doubt, in the course of recent years, Kumu has brought to light the links between the Düsseldorf School and the art of Russian and Nordic Countries. The theme of social injustice by German artists corresponds to the work of Peredvizhniki, as well as romanticism and naturalism in the literature of 19th century Europe.

Helena Risthein is an art historian, working at the Art Museum of Estonia as a lecturer.

Oskar Hoffmann

Man Reading a Newspaper

ca 1902

oil on canvas

Courtesy of the Art Museum of Estonia

Photo by Stanislav Stepashko